The Arch: Strength Through Unity

The arch is the natural way in which vertical loads are redirected sideways to bridge a span. To transfer these forces using materials that resist only compression, there is no other solution than to bend. Thus, arching seeks a path of compressive forces capable of fulfilling that mission of support and discharge.

The strategy employed by the arch is to assume a shape that allows it to behave as though it possesses more substance than it truly has. Its strength lies not in the amount of material it contains, but in the curve it adopts. The arch traces a continuous line of compression through space, optimizing its scarce material by arranging it along that very path.

United it Stands

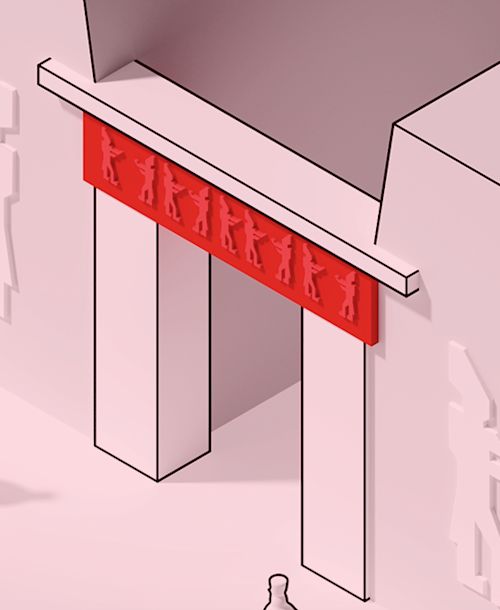

The arch is one of the clearest examples of unity in architecture — the triumph of many small parts collaborating to achieve a greater purpose.

None of these parts — the voussoirs — can do anything on its own, yet each knows how to work with its companions. Honoring its role, it bears the portion of the load that falls upon it and passes it on to the next in a seamless act of continuity. Together, they form a well-tuned orchestra.

We call the segment placed last, at the top, the keystone, because we believe it is the most important. But an arch is a democracy, and all voussoirs are equally necessary and substantial. None of them functions until they are all together. That is why we tend to think of the last one as the protagonist — the expert who arrives with the solution.

Yet, in truth, every voussoir is both the first and the last: if we were to build the arch starting at any point, it would always be the final piece, whichever it happened to be, that gave meaning to the whole. Not because it is superior, but because it completes the collective.

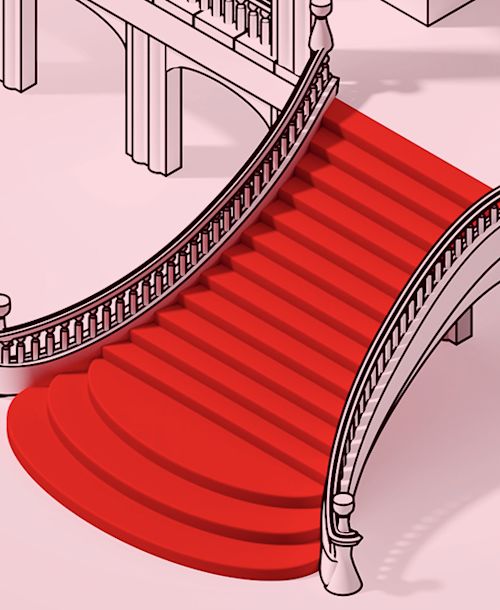

Since no part of the arch can resist anything until the structure is finished — not even to support itself — it requires a temporary crutch to lean on. This is the centering, a wooden frame shaped to the arch’s curve, which supports the voussoirs until the entire form is closed. Then, its mission accomplished, it quietly withdraws to its chambers.

A System in Balance

The arch is a system in equilibrium — a rare pirouette of loose pieces that do not collapse because it is the load itself that binds and sustains them. The very compression the arch must withstand is the same force that holds it together. And when the external load is light, the weight of the arch itself helps maintain its balance.

The arch was invented long before anyone knew the modern and substantial “theory of the arch.” Its builders understood what they were doing without knowing that they knew. Their knowledge was initiatory, their craft passed down through oral tradition — the arcane rules of tracing transmitted from master to apprentice, like a whispered spell.

Arches Through History

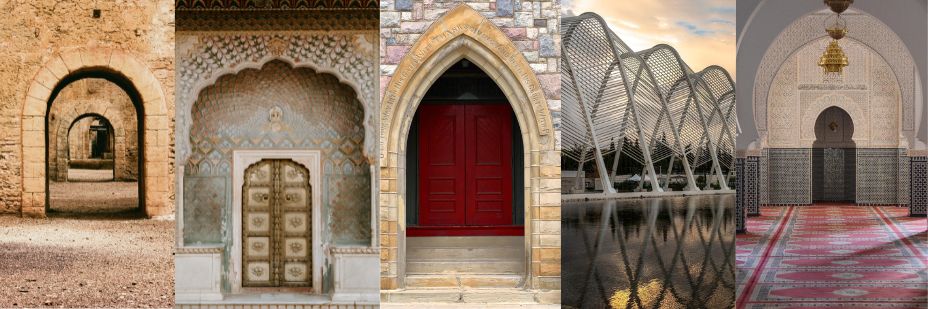

There are hundreds of shapes and kinds of arches — too many to list exhaustively — but a few deserve special mention.

The semicircular arch, shaped as a half-circle, is perhaps the first that comes to mind. Clean and elegant, it is the Roman — and later Romanesque and Renaissance — arch ‘par excellence.’ It has the sober grace of perfection, though not the most efficient form, as its upper part is too horizontal.

The pointed arch lacks continuous curvature, meeting instead in a sharp vertex at the top. It is much more efficient than the semicircular arch but sacrifices its classical serenity. It is typical of Gothic architecture and certain Eastern styles as well.

The parabolic arch is even more efficient than the pointed one, while retaining continuous curvature. The parabola is the inverse — or anti-funicular — curve that a suspended wire would assume under a uniformly distributed load. It was Gaudí’s favorite arch, admired both for its anti-funicular logic and for its sensual, anti-classical form.

The horseshoe arch extends beyond a half-circle, so it is narrower at the supports than at the center. In other words, its curve has a larger diameter than the gap it spans. Originating in Sassanid Persian architecture, it was later adopted by the Byzantines, the Visigoths, and the Umayyads of al-Andalus.

The lobed arch is pure fantasy — a fractal form, an arch traced from smaller sub-arches. The simplest are trilobed, while the more elaborate polylobed examples are strikingly ornate. Born in the Near East, they were later adapted as sophisticated variants within several architectural traditions.

These arches speak of cultures, functions, uses, intentions, tastes, and symbols. They reveal diverse ways of thinking, feeling, and building. It is astonishing that something so apparently simple can be so opulently complex.