The design of buildings that incorporate natural ventilation is a practice inspired by traditional techniques, now enjoying renewed relevance. This approach helps reduce energy consumption and improve living comfort, making a tangible contribution to contemporary sustainability goals. The fundamental principle of natural ventilation is to harness the laws of physics to promote air circulation and cooling without relying on mechanical systems.

Passive ventilation is more than just a technical solution — it is also an aesthetic and ethical principle. Integrating air — its movement, its variability, its lightness — into the architectural project means restoring a sensory and conscious dimension to the act of living. In an era when sustainability has become an imperative rather than an option, this ancient yet innovative strategy stands as one of the cornerstones of architecture that truly engages with the climate, reduces consumption, and enhances the well-being of its spaces.

Natural Ventilation: What It Really Means

A passive ventilation system harnesses natural physical phenomena such as wind and temperature gradients to introduce fresh air, expel hot air, and regulate humidity — maintaining comfortable conditions with little or no active energy input.

Key strategies include:

Cross ventilation, where air flows across the building through openings on opposite sides.

Stack effect, which uses the temperature difference between interior and exterior spaces to create upward air movement.

Combined ventilation, which merges cross ventilation and the chimney effect to maximize effectiveness in variable climates.

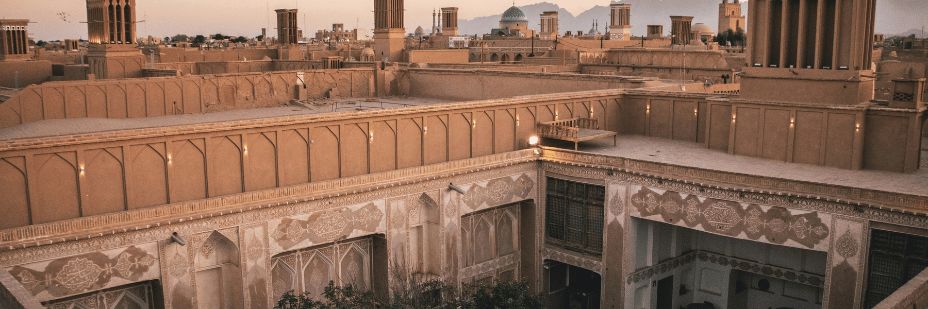

The Wisdom of Building: Natural Ventilation in Asian Vernacular Architecture

Long before mechanical systems and air conditioning, natural ventilation was an essential part of architecture. Vernacular building traditions around the world learned to interpret the climate and translate it into built form.

In India and Southeast Asia, traditional solutions offer remarkable lessons in balancing aesthetics and functionality:

Rajasthani havelis, with their inner courtyards and jalis (intricate stone or wooden screens), promote cross ventilation while filtering intense sunlight.

In Malaysia, traditional Malay houses built on stilts feature high-pitched roofs and openings under the ridge that use the chimney effect to expel hot air. Their raised structure also allows airflow beneath the floor, cooling the rooms.

In Indonesia, rumah adat houses are designed with permeable walls and large ventilated attics, providing comfort even in humid tropical climates.

These architectures were not only functional but also deeply symbolic: to live meant to coexist in harmony with air and light. The building itself breathed alongside its inhabitants.

Passive Ventilation in Traditional European Rural Architecture

In Europe, traditional approaches may be less poetic, but they are no less eloquent. In Alpine and Po Valley barns, wooden or brick shutters allowed natural airflow for drying crops. Meanwhile, in Mediterranean farmhouses, the combination of interior courtyards and thick walls represented an early form of bioclimatic design.

The courtyards encouraged natural air circulation through the temperature and pressure differences created between sunny and shaded areas. During the hottest hours of the day, warm air rose and was replaced by cooler currents from shaded zones or side openings — a simple yet effective way to generate convection and local breezes.

At the same time, thick stone or tuff walls provided excellent thermal storage, absorbing heat slowly during the day and releasing it gradually at night. This high thermal inertia kept indoor temperatures stable and reduced day–night fluctuations. All of this occurred without mechanical systems, relying instead on a deep, place-based construction wisdom.

Why Passive Ventilation Is Central to Sustainability

Natural ventilation is not a modern invention, but the continuation of ancient knowledge reinterpreted to meet today’s sustainability goals. Its advantages are multiple:

Reduction of energy consumption

In many modern buildings, heavy insulation and airtight envelopes can cause overheating in summer or humidity build-up. Well-designed natural ventilation reduces the need for mechanical cooling, leading to significant energy savings and lower CO2 emissions.

Occupant comfort and health

Air movement, balanced temperature, and controlled humidity are essential for well-being and quality of life. A natural and continuous exchange of air helps maintain healthier and more comfortable indoor environments.

Respect for the climatic and environmental context

Each climate, orientation, and urban setting presents specific opportunities. Natural ventilation takes advantage of local conditions, strengthening the connection between architecture and its surroundings.

Extended sustainability

The effectiveness of natural ventilation also depends on the envelope materials — their breathability and thermal inertia. True sustainability considers the entire life cycle of a building, not just its immediate energy performance.

Designing with Natural Ventilation: Key Considerations

Designing buildings that take full advantage of natural ventilation requires an integrated vision in which form, orientation, and materials interact with the local climate and prevailing air movements. This is not merely a technical solution, but a genuine design philosophy that places nature at the center of the architectural process — transforming wind and temperature differences into valuable resources.

Orientation and form

A building’s shape and orientation are among the most crucial factors. Slender, well-positioned structures that align with prevailing winds encourage cross ventilation, allowing air to flow evenly through interior spaces. Careful attention to interior layouts is equally important: avoiding obstacles that block airflow and ensuring clear, effective ventilation routes, even during the hottest months.

Openings

The type and placement of openings play a decisive role. Windows, grilles, doors, or skylights, calibrated in both height and orientation, help maximize natural airflow. Strategically positioned openings — on façades, roofs, or atriums — facilitate the entry of cool air and the release of warm air, maintaining a balanced indoor microclimate. To enhance the chimney effect, designs can integrate ventilated roofs, central atriums, or dedicated air shafts that generate vertical air movement and promote continuous air exchange.

Materials and the building envelope

Equally essential is the design of the building envelope, which should be responsive and dynamic. Breathable materials, adjustable shading systems, and plant-based architectural solutions help naturally regulate temperature, humidity, and air quality. These elements not only enhance comfort but also create a constant dialogue between inside and outside, turning the building into an active participant in the surrounding ecosystem.

Limitations and Challenges

Not every climatic or urban context allows for the exclusive use of natural ventilation. In areas with high humidity or in densely built environments, its effectiveness can be limited. This makes design sensitivity essential — along with accurate microclimate simulations and close collaboration between architects, engineers, and urban planners.

In such cases, a hybrid approach may be the best solution, combining natural ventilation with energy-efficient mechanical systems, ideally powered by renewable sources. This intelligent integration ensures consistent comfort and performance while keeping the ecological footprint to a minimum.

Natural Ventilation: A Silent but Powerful Ally

Designing with natural ventilation means conceiving architecture as a living organism — one that breathes, adapts, and interacts with its environment. Passive ventilation systems are neither an aesthetic whim nor a nostalgic return to the past. Designing buildings that converse with the wind restores meaning and dignity to the relationship between people, nature, and architecture.

When integrated thoughtfully from the earliest design stages, natural ventilation can enhance comfort, reduce energy consumption, and make a tangible contribution to a more sustainable future for all.